How the Romans invented central heating

Central heating feels like a modern convenience, yet its core principles were mastered nearly two thousand years ago. Long before boilers, radiators and underfloor heating systems, the Romans developed an ingenious method of warming buildings from below. Known as the hypocaust system, it was one of the most sophisticated building technologies of the ancient world, the foundation of many modern heating concepts – and in many ways – still in use today.

A hypocaust was an early form of central heating used in Roman villas, bathhouses and public buildings. Rather than heating individual rooms with open fires, the system generated heat in a single location and distributed it throughout the building. This approach allowed spaces to be heated evenly, efficiently and without smoke.

The word hypocaust comes from the Greek hypo (under) and kaustos (burnt), meaning “heat from below.” This description is literal because floors were raised above the ground on small pillars, creating a void where hot air could circulate.

At the heart of the system was the praefurnium, a furnace usually located outside the main building. Wood was burned here to generate hot air and gases. Instead of escaping directly into the atmosphere, this heat was channelled beneath the building.

Floors were supported on hundreds of small brick or stone pillars called pilae, typically around 60 centimetres high. The raised floor, or suspensura, allowed hot air to flow freely underneath. As the heat moved through this underfloor cavity, it warmed the stone or tile floor above, which then radiated warmth into the room.

To extend heating beyond the floor, many buildings also incorporated hollow wall tiles, known as tubuli. These vertical flues allowed hot air to rise up through the walls before exiting through roof vents. This ensured even heat distribution and helped draw air through the system, improving efficiency. The result was a form of radiant heating that warmed people, surfaces and spaces evenly, remarkably similar in principle to modern underfloor heating.

Where hypocausts were used

Hypocaust systems were most famously used in Roman bathhouses, where different rooms required different temperatures. The caldarium (hot room) was positioned closest to the furnace, while the tepidarium (warm room) and frigidarium (cold room) were progressively cooler.

However, hypocausts were not limited to baths. Wealthy Romans installed them in private villas, particularly in colder provinces such as Britain, Germany and Gaul. Excavations at sites like Fishbourne Roman Palace and Bath in the UK reveal extensive hypocaust remains, demonstrating how widespread and effective the system was.

While hypocausts delivered impressive comfort, they were far from simple to build or maintain. Construction required precise planning, robust materials and skilled labour. Floors had to be strong enough to support furniture and occupants while remaining thin enough to conduct heat effectively.

Fuel consumption was significant. Large quantities of wood were needed to keep the furnace burning and slaves or workers were required to operate and maintain the system. Soot buildup in flues had to be managed, and uneven airflow could lead to cold spots. For these reasons, hypocausts were largely reserved for public buildings and the elite.

Following the decline of the Roman Empire, hypocaust technology largely disappeared in Europe. Knowledge of large-scale central heating was lost as building techniques became simpler and fuel scarcer. For centuries, heating reverted to open fires and individual stoves.

It wasn’t until the 18th and 19th centuries that central heating began to re-emerge, first in industrial and institutional buildings and later in homes. When it did, many of the same principles pioneered by the Romans were rediscovered.

The influence on modern heating systems

Modern underfloor heating is the clearest descendant of the hypocaust. Instead of hot air from a furnace, today’s systems use warm water pipes or electric elements embedded beneath the floor. Heat rises gently and evenly, eliminating cold spots and reducing the need for radiators.

The Roman concept of radiant heat, warming surfaces rather than air alone, is now recognised as one of the most comfortable and energy-efficient ways to heat a space. The use of thermal mass, such as stone or concrete floors, to store and release heat slowly is another idea lifted directly from Roman practice.

Even modern central heating layouts echo the hypocaust model. A single heat source distributes warmth throughout a building via a network of channels, whether those are pipes, ducts or cables. Zoning, heat control and airflow management all have ancient parallels in Roman bathhouse design.

The hypocaust reminds us that effective building services are as much about design as technology. Roman engineers understood airflow, material behaviour and human comfort without modern sensors or software. Their systems worked because they were integrated into the building fabric from the outset.

In today’s push for low-carbon, energy-efficient buildings, these lessons feel newly relevant. Passive design, thermal mass and radiant heating are once again central to architectural thinking, proof that innovation sometimes means rediscovering old ideas.

Roman hypocausts were more than clever heating systems - they represented a holistic approach to building comfort. By centralising heat, distributing it evenly and embedding it into architecture, the Romans set a precedent that still shapes how we heat buildings today.

While modern systems are cleaner, safer and more controllable, the fundamental idea remains unchanged. Every time we walk across a warm floor on a winter morning, we’re experiencing a technology that traces its roots back to ancient Rome.

Central heating may feel modern, but its origins lie beneath the stone floors of Roman bathhouses, where engineers first proved that comfort could be designed into buildings, not added as an afterthought.

Additional Articles

Why modern builders still use tools invented thousands of years ago

Walk onto a modern construction site and you will see plenty of laser levels, drones, tablets and power tools. Yet look a little closer and something unexpected becomes clear. Alongside all this...

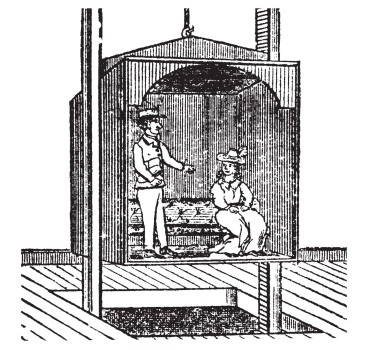

Read moreThe elevator that changed the world when Elisha Otis cut the rope

Today, stepping into a lift is one of the most routine acts of modern life. We press a button, glance at the floor indicator, and trust, almost without thinking. that a metal box will safely carry us...

Read more

Building without blueprints or how medieval cathedrals rose without drawings

During the medieval period, some of Europe’s most ambitious and enduring buildings were constructed without anything resembling modern architectural plans. Between the 11th and 15th centuries, vast...

Read more