Building without blueprints or how medieval cathedrals rose without drawings

During the medieval period, some of Europe’s most ambitious and enduring buildings were constructed without anything resembling modern architectural plans. Between the 11th and 15th centuries, vast stone cathedrals rose across France, England, Germany and beyond, built largely from memory, tradition and shared craft knowledge rather than formal drawings.

The builders of structures such as Chartres Cathedral in northern France or Canterbury Cathedral in England (pictured above) did not rely on comprehensive design documents. Instead, construction knowledge was held by master masons who learned their trade through years of apprenticeship. Architectural understanding was transmitted orally and practically, passed from one generation to the next through hands-on experience rather than written instruction.

Medieval builders operated within a deeply ingrained architectural tradition. Romanesque and later Gothic construction followed established proportions and forms that were widely understood within the trade. A master mason working in 12th-century France would instinctively understand how to proportion a nave, how to construct pointed arches and how to distribute weight through stone vaults.

At Notre-Dame de Paris, construction began in 1163 and continued well into the 14th century. Despite the absence of formal drawings, the builders created a structure of remarkable harmony and balance. Full-scale templates were occasionally scratched onto tracing floors near the site to guide the shaping of stone ribs or arches, but these were temporary tools, not permanent plans. The cathedral itself emerged phase by phase, guided by precedent rather than prescription.

This method allowed medieval buildings to evolve organically. When material quality changed or structural challenges emerged, builders adapted the design on site. Flexibility was not a flaw, but a necessity, allowing construction to respond to real conditions rather than fixed drawings.

The Master Mason

In medieval Europe, the master mason occupied a role that combined architect, engineer, and site manager. At York Minster, construction began around 1220 and continued until 1472. Over this period, multiple master masons oversaw different phases of work, each interpreting the building’s direction through their own experience.

Rather than producing drawings, the master mason communicated design intent verbally and through demonstration. Authority came from reputation and skill, not paperwork. When leadership changed, subtle changes in style often followed. At York Minster, the transition from Early English Gothic to Decorated Gothic and later Perpendicular Gothic is clearly visible, reflecting changes in both fashion and personnel.

This approach made cathedrals collaborative achievements rather than the vision of a single designer. Buildings became records of accumulated expertise, shaped by many hands over many decades.

Construction That Spanned Lifetimes

Few medieval cathedrals were completed within a single generation. Cologne Cathedral in Germany (pictured below) is one of the most striking examples. Construction began in 1248 but stalled in the 16th century, leaving the building unfinished for over 300 years. Work did not resume until the 19th century, and the cathedral was finally completed in 1880, more than 630 years after it began.

Similarly, Milan Cathedral, construction of which started in 1386, took nearly six centuries to complete, with its final details only finished in the 20th century. Builders who laid the foundations could not possibly have imagined the finished structure. Their work was an act of faith in both craftsmanship and continuity.

In medieval society, this was accepted as normal. Cathedrals were civic and spiritual projects that belonged to communities rather than individuals. Each generation contributed what it could, knowing that completion lay far in the future.

Because construction took so long, many cathedrals showcase a mixture of architectural styles. Canterbury Cathedral, rebuilt after a fire in 1174, offers a clear example. The eastern end was constructed in an early Gothic style under the master mason William of Sens, while later sections reflect English Gothic traditions developed decades later.

At Chartres Cathedral,(pictured below) much of the structure was rebuilt rapidly after a devastating fire in 1194, yet even here construction extended into the 13th century. The result is a building that appears unified but still contains subtle variations in detailing and proportion, revealing different phases of work.

Rather than striving for stylistic consistency, medieval builders valued continuity of purpose. The cathedral was a living project, shaped by time, resources, and changing artistic ideals.

Faith, Patience, and Collective Purpose

Cathedrals were more than architectural achievements; they were expressions of faith and civic identity. Entire towns contributed labour, materials, and funding. At Salisbury Cathedral, built remarkably quickly between 1220 and 1258, speed was the exception rather than the rule, made possible by strong financial backing and stable conditions.

Even so, most medieval builders worked without recognition. Their names rarely survive, and few monuments credit individual craftsmen. The work was seen as service rather than self-expression. Construction was undertaken for the glory of God and the benefit of future generations.

This patience contrasts sharply with modern expectations. Medieval builders accepted delays, uncertainty, and change as part of the process. Time was not an enemy to be defeated, but a resource to be used.

The survival of these buildings is a testament to the effectiveness of their construction methods. Many medieval cathedrals have stood for over 800 years, enduring war, weather, and social change. Their longevity reflects a commitment to durability, craftsmanship and long-term thinking.

While modern construction rightly prioritises safety, efficiency, and documentation, medieval practice reminds us of the value of skilled judgment and adaptability. These builders trusted their materials, their experience and each other.

The fact that medieval builders could erect structures like Notre-Dame de Paris, York Minster, and Cologne Cathedral without drawings and commit generations to their completion, remains one of history’s greatest construction achievements. These buildings are not merely relics of the past - they are enduring lessons in patience, collaboration and belief in the future.

Set in stone and stained glass, medieval cathedrals stand as proof that great construction is not only about plans and technology, but about people, tradition and the willingness to build for a world beyond one’s own lifetime.

Additional Articles

Why modern builders still use tools invented thousands of years ago

Walk onto a modern construction site and you will see plenty of laser levels, drones, tablets and power tools. Yet look a little closer and something unexpected becomes clear. Alongside all this...

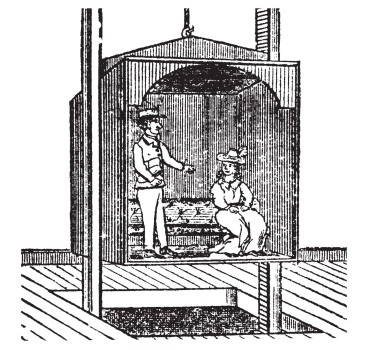

Read moreThe elevator that changed the world when Elisha Otis cut the rope

Today, stepping into a lift is one of the most routine acts of modern life. We press a button, glance at the floor indicator, and trust, almost without thinking. that a metal box will safely carry us...

Read more

How the Romans invented central heating

Central heating feels like a modern convenience, yet its core principles were mastered nearly two thousand years ago. Long before boilers, radiators and underfloor heating systems, the Romans...

Read more