Why Gargoyles were the original rainwater management systems

Gargoyles are purpose-built rainwater spouts - ingenious, sculpted drainpipes that kept torrents off fragile masonry long before gutters and downpipes existed. In the wet, wind-lashed climates where Gothic architecture flourished, gargoyles were essential building services hidden in plain sight. They projected water clear of walls and foundations, slowed decay of mortar joints and safeguarded vaults and interiors from damp. The monsters made maintenance possible.

A true gargoyle channels roof runoff through a carved conduit and throws it several feet from the façade, usually through an open mouth. The physics is simple and effective - collect water from steep lead or tile roofs, route it through internal channels and project it clear of vertical stonework. That last step is vital. Water cascading down walls mobilises salts, erodes pointing, saturates bedding and accelerates frost damage. By “launching” water away, gargoyles cut the wetting cycle dramatically, an early, elegant form of building envelope protection.

To do this well, masons gave gargoyles long throats and pronounced overhangs. Many were set on parapets or cornices, integrated with hidden gutters that fed their inlets. Profiles were carefully pitched so water wouldn’t pool and freeze. The spouts had drip details to break capillary action and their mouths flared to disperse flow and reduce staining. It was hydraulic engineering dressed as theatre.

Not every carved creature aloft is a gargoyle. If it doesn’t move water, it’s a grotesque, still expressive, but purely decorative. Regional terms abound - in Somerset and parts of the West Country, short, squat roof figures are often called “hunky punks,” almost always non-draining ornaments. The confusion is understandable - both forms share the same visual vocabulary of beasts, demons, and caricatures - but only the gargoyle serves the building’s drainage strategy.

Notre-Dame de Paris

The world’s most famous gargoyles are those brooding chimeras perched on Notre-Dame’s towers. Many of the creatures people know best were added or reimagined during Eugène Viollet-le-Duc’s 19th-century restoration, but they sit in a medieval lineage of functional spouts that kept the cathedral’s limestone skin intact. Look closely and you’ll see the pragmatic logic beneath the drama - mouths angled out beyond the cornice, throats pitched to keep velocity and drip edges that snap falling water into droplets so it won’t track back across the stone. They are performance details, executed with sculptural bravado.

Laon, Reims and the Northern Masters

Northern France, where rainfall and freeze-thaw cycles punish façades, developed gargoyles into an art. Laon Cathedral’s menagerie includes long-necked oxen heads that double as spouts and as a visual nod to the animals that hauled stone up the hill. At Reims, gargoyles align with flying buttresses and string courses, placed where roof drainage converges. These positions aren’t arbitrary - they correspond to hidden gutter falls and valley junctions. The lesson for modern architects is clear - the best ornament grows from and clarifies building performance.

Across England, you’ll find superbly practical gargoyles paired with exuberant grotesques. Lincoln and York host elongated spouts with projecting troughs that sling water beyond deeply articulated façades. At Westminster, where much carving is decorative, the true gargoyles still tell a performance story - long projection, tapered chutes and strategic placement at water collection points. Even where later gutters were retrofitted, original gargoyles often remained as overflow.

The enigmatic Sheela-na-gigs of Britain and Ireland, exaggerated female figures carved on medieval churches, are frequently mistaken for gargoyles. They are not water spouts, but they reinforce a point - medieval façades carried narrative, moral, and didactic content atop a base of hard-nosed building physics. The coexistence of symbol and service explains why gargoyles endured - they performed, and they spoke.

Material, craft and maintenance

Most gargoyles are carved from the same stone as their host building - limestone, sandstone, or tufa - chosen for workability and local availability. That choice binds them to the wall aesthetically, but exposes them to the harshest duty cycle on the structure - repeated saturation and rapid drying, wind-driven rain, ice and acid deposition. Historically, masons protected spouts with subtle details - sacrificial noses, internal slopes to keep water moving, and jointing that shed, rather than trapped moisture.

Today, conservation teams test flow, clear debris and repair mortar to keep gargoyles working. In some cases, leads or stainless liners are inserted in the throat to reduce erosion while preserving the original profile. The conservation principle mirrors the medieval one: performance first, expressed as craft.

Study a well-designed gargoyle and you can read a hydraulic brief carved into its silhouette. The inlet mouth is slightly constricted, maintaining velocity - the throat length provides a consistent, self-cleaning channel - the outlet flares to throw water clear and the lower jaw lip forms a drip. The projection length correlates with cornice depth and wind patterns - too short and splashback stains the façade, too long and the lever arm risks cracking. Many gargoyles also tilt slightly outward to prevent standing water after a storm. The profile is sculpture, yes, but it’s also a flow diagram.

Gothic roofs were steep to shed water and snow quickly. Lead gutters and timber valleys concentrated runoff at regular bay intervals - perfect places to station a gargoyle. The repetition of spouts along a nave or choir isn’t just decorative rhythm - it maps the roof’s drainage grid. Walk a cathedral close in a storm and you’ll hear the cadence of discharge as spouts fire in sequence, each protecting a kiln-dried, lime-pointed skin that otherwise would dissolve under centuries of rainfall.

What gargoyles teach modern designers

First, make water visible. Gargoyles dramatise what the building is doing to protect itself, turning a liability into a legible performance feature. Second, separate water from the envelope decisively. Throw it clear - don’t compromise with minimal overhangs or flat profiles that stain and saturate. Third, align systems. Roof geometry, hidden gutters and spout placement work as one. When the roof is detailed without a discharge strategy, the façade pays.

Contemporary architecture often hides its plumbing. Yet the “honest detail” ethos -celebrating how a building breathes, drains and moves - has renewed relevance in an era of cloudbursts and climate uncertainty. Modern scuppers, spouts and rain chains can borrow the gargoyle’s lesson.

Where gargoyles clog with leaves or pigeon debris, water backs up into parapets, saturating cores and rusting cramps. Where replacement carvings shorten projections for aesthetics, splashback returns, streaking the stone and re-wetting mortar. Where cement mortars replace lime at seating joints, the rigid interface traps moisture and accelerates spalling. Each failure recites the same law - water will find the path of least resistance - design that path, or it will choose your masonry.

Gargoyles as early sustainable design

In sustainability terms, gargoyles are durable, low-tech and passive. They require no pumps, no controls and almost no material beyond the parent stone. Their maintenance demands are predictable - keep channels clear, repoint with compatible lime when needed, repair sacrificial tips. Over centuries, that’s an extraordinarily efficient life-cycle profile. They also contribute to heritage value and place identity - social sustainability before the term existed.

While cathedrals made them famous, gargoyles appear on town halls, collegiate buildings, and occasionally, grand houses. Smaller domestic versions - projecting spouts in timber or stone - perform the same work at a different scale. In some Alpine and Central European traditions, zoomorphic spouts in wood shed meltwater far from log walls.

The medieval genius was to fold necessity into meaning. A dragon that spews rain is both a hydraulic and a metaphor - chaos tamed and repurposed for the common good. The best gargoyles exploit this doubleness. They lighten vast façades with wit and menace while prosecuting a relentless, practical task. That fusion of utility and narrative is why they continue to fascinate and why their lesson remains useful - performance can be beautiful -and beauty can perform.

Strip away the mythology and a gargoyle is the most pragmatic of ornaments. It takes the destructive force that ruins buildings – water - and gives it a safe, spectacular exit. In a single element, medieval builders solved a technical problem, expressed a worldview and bequeathed a masterclass in visible performance. Modern designers facing cloudbursts, rising maintenance costs and stricter envelope standards can take a cue from the creatures on the parapet - throw the water clear, tell the truth about how you do it, and let function lead the form. The monsters were engineers all along.

Additional Articles

Why modern builders still use tools invented thousands of years ago

Walk onto a modern construction site and you will see plenty of laser levels, drones, tablets and power tools. Yet look a little closer and something unexpected becomes clear. Alongside all this...

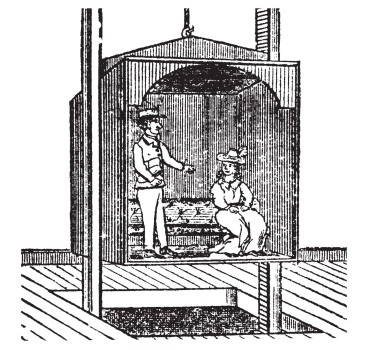

Read moreThe elevator that changed the world when Elisha Otis cut the rope

Today, stepping into a lift is one of the most routine acts of modern life. We press a button, glance at the floor indicator, and trust, almost without thinking. that a metal box will safely carry us...

Read more

How the Romans invented central heating

Central heating feels like a modern convenience, yet its core principles were mastered nearly two thousand years ago. Long before boilers, radiators and underfloor heating systems, the Romans...

Read more