Why builders turned to astrology in the Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, the science of construction often shared a surprising partnership with the stars. While today’s builders rely on lasers and structural modelling software, their medieval predecessors sometimes looked skyward for guidance - not just for inspiration, but for instructions. In certain cathedrals, castles and city walls across Europe, the foundation stones were laid not simply when materials arrived or schedules aligned, but when the heavens said it was right to do so.

This wasn’t a matter of superstition alone. The role of astrology in medieval construction reveals how deeply entwined religion, cosmology and architecture were in the worldview of the time. Builders weren’t just erecting walls - they were constructing sacred alignments, embedding celestial harmony into stone and mortar.

In the Middle Ages, astrology was regarded as a scholarly and legitimate field, often studied alongside medicine, mathematics and astronomy. The movement of the planets was believed to influence earthly events - weather, harvests, health, even politics. It was entirely rational, by the standards of the time, to believe the timing of a construction project could determine its success or failure.

Certain days, dictated by the position of the moon or planets, were deemed more auspicious than others. Builders and patrons - particularly in ecclesiastical or royal commissions - consulted astrologers or clerics who understood celestial charts. A foundation stone laid under a favourable planetary configuration could invite divine blessing or cosmic harmony. A poorly timed ceremony might invite structural misfortune or spiritual unrest. In this context, astrology wasn’t mystical theatre - it was risk management.

Cathedrals, castles and cosmic order

One of the most striking examples comes from the construction of cathedrals. These were not merely churches - they were monumental expressions of spiritual belief, often aligned with astronomical events such as solstices or equinoxes. The orientation of a cathedral -usually with its apse pointing east - was sometimes determined in concert with astrological observations to maximise symbolic and literal light. The moment the foundation was set mattered as much as the site itself.

Take, for example, the rebuilding of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London following the Great Fire of 1666. While post-medieval in date, it reflects the continuation of older traditions. The architect Christopher Wren, steeped in both classical knowledge and the scientific thinking of his day, is believed to have considered astrological timing when designing key phases of the project. Earlier medieval practices would have leaned even more heavily on these cosmic considerations.

Castles, too, occasionally followed astrological advice, especially in the early laying out of defensive walls or towers. A royal astrologer might be consulted before a cornerstone was laid, not only for protection, but to align a ruler’s new stronghold with favourable planetary influences - perhaps to symbolise strength under Mars, or peace under Venus.

The Church held a complex view of astrology. While condemning fortune-telling and divination, it tolerated and often employed astronomical astrology when framed as a way to understand God’s ordered universe. Many cathedral schools and monasteries had scholars who studied the stars as part of the quadrivium (the higher division of the medieval liberal arts). These studies included arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy - disciplines interconnected in medieval cosmology.

Astrology’s inclusion in learned society lent it credibility in architectural planning. Bishop-builders, like Suger of Saint-Denis in 12th-century France, were often at the forefront of such integrations, blending theological vision with mathematical precision and celestial symbolism.

Astrological manuals for builders

There is evidence that builders and patrons used specific manuals that included not just architectural drawings or logistical checklists, but astrological charts. These guided the timing of key construction events such as foundation laying, cornerstone placement and even ceremonial dedications.

The 13th-century text Secretum Secretorum, attributed (incorrectly) to Aristotle and widely circulated in Europe, contains astrological advice applied to kingship and decision-making, including building works. Similarly, works by Islamic scholars - translated into Latin in centres like Toledo - contributed to the spread of astrological principles into European technical and philosophical thought.

Behind the practical use of astrology in medieval building was a deeper idea - that architecture could reflect the divine order of the universe. This notion of macrocosm and microcosm - that the human world mirrored the celestial - was a driving force in Gothic architecture. Cathedrals were not just houses of worship, but cosmic diagrams, expressions in stone of the heavenly city.

To align a building with the stars was, in essence, to link the temporal world with the eternal. Astrological timing was just one way to do that. The result was architecture that aimed to channel more than physical force - it sought to bring the material and the metaphysical into harmony.

By the late Renaissance, astrology began to lose its scholarly standing. The scientific revolution, with its emphasis on empirical observation and scepticism of celestial influence, gradually pushed astrological methods to the fringes. But the legacy of astrology in medieval construction lives on in the alignments, symbols and rituals embedded in Europe’s oldest structures.

Modern archaeology and architectural history have begun to recover this hidden layer of meaning. Where once a builder’s spade might have struck earth to the sound of a chant and the reading of a star chart, today we dig with a more secular spade. But beneath the foundations of many medieval buildings lies not just stone, but the residue of a worldview in which heaven and earth were never far apart.

Additional Articles

Why modern builders still use tools invented thousands of years ago

Walk onto a modern construction site and you will see plenty of laser levels, drones, tablets and power tools. Yet look a little closer and something unexpected becomes clear. Alongside all this...

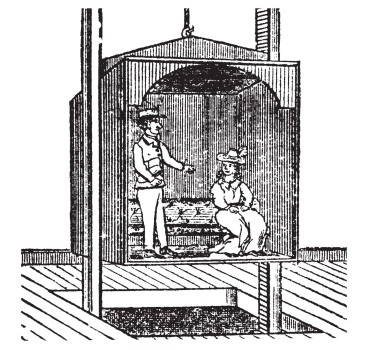

Read moreThe elevator that changed the world when Elisha Otis cut the rope

Today, stepping into a lift is one of the most routine acts of modern life. We press a button, glance at the floor indicator, and trust, almost without thinking. that a metal box will safely carry us...

Read more

How the Romans invented central heating

Central heating feels like a modern convenience, yet its core principles were mastered nearly two thousand years ago. Long before boilers, radiators and underfloor heating systems, the Romans...

Read more