How Victorian engineers recycled old warships into building materials

The Victorian age is remembered as a period of invention, rapid industrial growth and bold engineering projects that changed Britain forever. Railways criss-crossed the country, docks expanded and cities filled with new housing, bridges and factories. Yet behind these monumental works lay a little-known, but fascinating practice – where Victorian engineers recycled decommissioned warships and turned their hulks into building materials.

At a time when timber, iron and stone carried immense cost, the reuse of dismantled naval vessels offered an unexpected, but highly effective source of raw materials. What began as a practical solution to waste and scarcity also reflected the ingenuity of engineers in an era where nothing was casually discarded.

Britain’s naval dominance in the 18th and 19th centuries produced hundreds of wooden warships built to defend trade routes and project imperial power. These ships, often made from prime oak and elm, consumed vast amounts of timber during construction - the largest vessels requiring the equivalent of several hundred acres of mature woodland.

However, by the mid-19th century, the rapid shift from sail to steam power and from wood to iron hulls rendered many wooden warships obsolete. Rather than allow these formidable vessels to rot away in dockyards, naval authorities and engineers dismantled them and sold the material for reuse.

The process was surprisingly thorough. Planking, beams, copper fastenings and iron fittings were carefully stripped and resold. Oak and elm, once part of gun decks and hulls, were recut into beams, floorboards and even furniture. Ship’s timbers, pre-seasoned by years of exposure to saltwater, proved remarkably durable in construction projects on land.

Ship timber in Victorian architecture

Examples of recycled warship timber appeared in a wide range of Victorian buildings. In London, large beams from decommissioned vessels were repurposed into warehouses and factories along the Thames, where their strength and resistance to damp conditions made them particularly valued.

In smaller towns and villages, ship oak found its way into cottages, inns and even churches. Some church roofs constructed in the mid-19th century incorporated curved timbers taken from a ship’s hull, giving them distinctive arches not dissimilar to the vessel from which they were salvaged. There are documented cases of altar rails and pews fashioned from dismantled warships, a subtle blending of military and spiritual heritage.

Engineers also used ship timber in more utilitarian projects. Railway sleepers, bridge supports and dock structures were all reinforced with wood from decommissioned ships. At a time when Britain’s rail network was expanding at breakneck speed, this recycled resource proved invaluable.

Iron and Copper

It wasn’t just wood that found a second life. Old warships were treasure troves of iron, lead and copper. Copper sheathing, originally nailed to hulls to protect against shipworm and marine growth, was stripped and smelted down for use in roofing, plumbing and industrial machinery.

Iron fittings - from anchors to fastenings - were melted and recast into girders and supports for Victorian construction. At a time when iron was becoming the backbone of modern industry, recycled naval metal provided both a practical and economic advantage.

One famous example of copper reuse came from HMS Implacable, a Napoleonic-era warship captured from the French. When she was finally dismantled in the 20th century, copper fittings were found to have been incorporated into various civic projects during the Victorian age, a reminder of how thoroughly ships were stripped for value.

There was also a symbolic dimension to this recycling. Using the timbers of once-proud warships in civic buildings tied communities to Britain’s naval heritage. Beams that had once supported cannons at Trafalgar could now support the roof of a town hall or church, embedding a sense of history and pride into the very fabric of everyday life.

In some cases, the provenance of the wood was highlighted deliberately. Public houses named “The Ship” or “The Victory” boasted interior fittings crafted from naval oak. Furniture makers advertised that their tables and chairs had been made from timber “that once sailed with Nelson.” These links to naval glory proved commercially popular, giving ordinary people a tangible connection to Britain’s maritime story.

Early sustainability in the age of industry

Recycling warships was, at its core, an early form of sustainability. While Victorians did not frame the practice in modern environmental terms, they instinctively understood the value of conserving resources. Timber shortages were a recurring problem in the 19th century, particularly as shipbuilding and railway expansion consumed vast quantities of wood. By salvaging oak and elm from redundant ships, engineers not only saved money, but also reduced pressure on dwindling natural supplies.

It is striking to note that while the Victorian era is often associated with smoke-belching factories and industrial waste, practices like ship recycling reveal a parallel culture of thrift and resourcefulness. Engineers saw waste not as an inevitability but as an opportunity.

Some of these recycled materials remain in use today, quietly hidden in buildings across Britain. Architectural surveys have uncovered naval timbers in 19th-century warehouses, civic halls, and churches. Their durability has allowed them to outlast much of the fabric around them, a testament to the quality of both the original shipbuilding and the Victorian recycling process.

Modern conservationists often marvel at how well these timbers have performed. Saltwater exposure, once thought to weaken wood, in fact hardened it against rot. As a result, beams cut from 18th-century warships sometimes remain in serviceable condition more than 200 years later.

The story of Victorian engineers recycling warships into building materials highlights a side of history often overlooked. These engineers were not just builders of new infrastructure, but masters of adaptation, finding ways to give obsolete resources a new lease of life. From cottages roofed with ship timbers to factories framed with naval iron, Britain’s built environment absorbed the remains of its naval past in ways both practical and symbolic.

Today, as we grapple with questions of sustainability and resource use, the Victorians’ approach carries a surprising resonance. They remind us that the materials of yesterday can shape the structures of tomorrow - and that ingenuity lies not only in what we create, but in how we reuse what we already have.

Additional Articles

Why modern builders still use tools invented thousands of years ago

Walk onto a modern construction site and you will see plenty of laser levels, drones, tablets and power tools. Yet look a little closer and something unexpected becomes clear. Alongside all this...

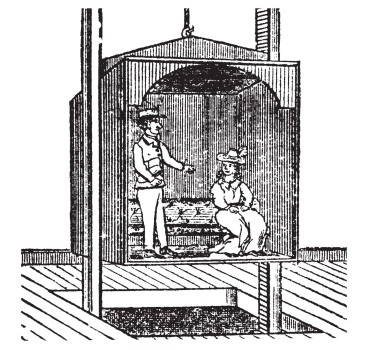

Read moreThe elevator that changed the world when Elisha Otis cut the rope

Today, stepping into a lift is one of the most routine acts of modern life. We press a button, glance at the floor indicator, and trust, almost without thinking. that a metal box will safely carry us...

Read more

How the Romans invented central heating

Central heating feels like a modern convenience, yet its core principles were mastered nearly two thousand years ago. Long before boilers, radiators and underfloor heating systems, the Romans...

Read more