Buildings made of salt and why it’s possible

When we think of building materials, we tend to picture stone, timber, steel, concrete, or glass. Salt, on the other hand, conjures images of dinner tables and seaside breezes rather than walls, vaults and chapels. Yet across the world, remarkable buildings have been carved out of or constructed with salt. These structures, both practical and breathtakingly beautiful, show that salt is far more than just a seasoning - under the right conditions, it can be a durable, workable and even an inspiring building material. But how is it possible to build with something so seemingly fragile? And why did humans choose salt for construction in the first place? The answers lie in geology, history and engineering ingenuity.

Salt, or sodium chloride, is one of the most abundant minerals on Earth. Vast underground deposits were created millions of years ago when ancient seas evaporated, leaving behind thick beds of crystallised salt. These deposits, often hundreds of metres deep, can be mined much like rock.

When freshly cut, rock salt is solid, heavy, and surprisingly strong. In fact, in areas with low humidity, it can remain intact for centuries. Its crystalline structure reflects light in unique ways, creating shimmering, almost translucent effects when used in construction.

Unlike stone or timber, salt is self-preserving under the right conditions. Salt mines, sealed away from air and moisture, often remain structurally sound for decades or even centuries. This explains why some of the world’s most impressive salt-built spaces are underground, where natural humidity control prevents the salt from dissolving.

The Salt Cathedral of Zipaquirá

One of the most famous examples of building with salt lies deep beneath Colombia. The Salt Cathedral of Zipaquirá, located about 200 metres underground, was carved directly into the walls of a former salt mine.

First constructed in the 1950s (and expanded in the 1990s), the cathedral is not built with blocks of salt but rather carved entirely from the existing salt deposits. The miners hollowed out vast chambers and sculpted altars, crosses and even chandeliers from the rock salt itself.

Today, it can hold up to 8,000 people and is considered both an engineering marvel and a spiritual sanctuary. The glowing salt walls, illuminated by carefully designed lighting, create an ethereal atmosphere. It’s an example of how salt, when used underground, can rival stone in its grandeur and durability.

Wieliczka Salt Mine

Poland’s Wieliczka Salt Mine, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, provides another extraordinary example. Dating back to the 13th century, the mine extends for more than 287 kilometres of tunnels, some of which have been transformed into chapels, halls and galleries.

Like Zipaquirá, the Wieliczka chapels are carved directly into salt. The Chapel of St. Kinga, often called “the underground salt cathedral,” features salt chandeliers, salt altars and even religious statues sculpted from salt crystals. The level of detail is staggering and the structures have survived remarkably well thanks to the naturally dry, stable environment underground.

In both Colombia and Poland, the salt-built chapels are not just places of worship, but also major tourist attractions, drawing millions each year. They highlight the cultural as well as architectural potential of salt as a building medium.

Why build with salt?

At first glance, constructing with salt seems impractical - after all, it dissolves in water. But several reasons explain why humans have turned to salt. In regions with massive salt deposits, the material was literally on hand. Mining it for trade left behind vast caverns, which could be adapted into usable spaces with little additional material cost.

Salt is also softer than most stones, making it easier to carve intricate designs. This made it ideal for creating underground chapels, reliefs and decorative elements. When kept dry, salt structures also remain stable and strong. Underground, where exposure to moisture is limited, salt can endure for centuries. Furthermore, salt reflects and refracts light in unique ways, creating glowing, almost magical interiors. This quality has made salt-built spaces not only functional but also visually stunning.

Modern experiments with salt architecture

While most salt-built structures are subterranean, some modern architects and engineers are exploring salt as a surface-level building material. One example comes from the Middle East, particularly in places like Iran, where salt deserts provide an endless supply of raw material. Experimental projects have used compressed salt bricks, treated with surface coatings, to construct small-scale buildings. The idea is that in arid climates with minimal rainfall, salt could serve as a cheap, sustainable building resource.

Similarly, design studios and universities have investigated salt’s potential for temporary structures at art festivals and expos. The natural crystalline beauty of salt bricks makes them striking, while their impermanence aligns with the temporary nature of such installations.

There is even ongoing research into salt-based concrete alternatives, where salt minerals are mixed with other binders to reduce reliance on traditional cement. Though far from mainstream, these experiments hint at a future where salt could play a role in sustainable architecture.

Of course, salt is not without its problems. Its greatest strength underground - durability in dry, controlled conditions - becomes its greatest weakness when exposed to rain, humidity, or fluctuating climates. Salt is highly hygroscopic, meaning it absorbs water from the air. This can lead to surface erosion, crumbling and eventually structural collapse if not properly managed.

Surface-level salt structures therefore require protective treatments, regular maintenance, and often climate-controlled environments. This explains why most large-scale salt architecture projects are underground, where nature itself provides the necessary preservation.

Another issue is environmental: salt mining can be ecologically disruptive, and the reuse of salt as a building material must be carefully weighed against its impacts on landscapes and ecosystems.

Healing and health

Salt-built spaces have also been associated with health benefits. The microclimate in salt mines is believed to improve respiratory conditions such as asthma and allergies. This has given rise to “salt therapy” or halotherapy, where patients spend time in specially constructed salt rooms.

In places like the Wieliczka mine, health resorts operate deep underground, offering visitors the chance to breathe purified, mineral-rich air while surrounded by salt walls. While the science is debated, the popularity of such therapies underscores another dimension of salt architecture - its link to wellness.

Buildings made of salt may sound like something out of a fairytale, but they have been part of human ingenuity for centuries. From the awe-inspiring cathedrals of Zipaquirá and Wieliczka to modern-day experiments with salt bricks in desert regions, salt continues to challenge our assumptions about what architecture can be.

While practical limitations prevent salt from replacing traditional materials, its aesthetic, cultural, and symbolic power is undeniable. Salt-built spaces remind us of the intimate relationship between geology and architecture - how the Earth itself can become both the canvas and the building block.

Salt is one of humanity’s oldest resources, tied to food, trade and survival. Its surprising use in architecture reveals both practicality and poetry - practical because it made use of abundant materials in regions rich with deposits and poetic because the luminous, crystalline quality of salt transforms interiors into otherworldly sanctuaries.

From underground chapels that feel like cathedrals carved from light to modern experiments in sustainable salt-based building, the story of salt architecture shows how even the most unlikely materials can inspire human creativity. It proves that innovation often begins with looking at what’s right beneath our feet - sometimes, quite literally, in the grains of salt left behind by ancient seas.

Additional Articles

Why modern builders still use tools invented thousands of years ago

Walk onto a modern construction site and you will see plenty of laser levels, drones, tablets and power tools. Yet look a little closer and something unexpected becomes clear. Alongside all this...

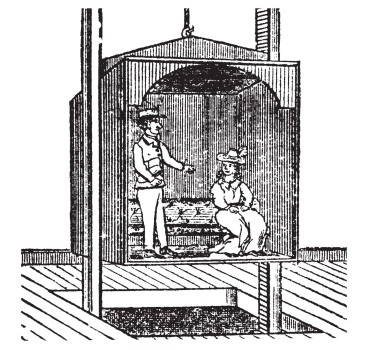

Read moreThe elevator that changed the world when Elisha Otis cut the rope

Today, stepping into a lift is one of the most routine acts of modern life. We press a button, glance at the floor indicator, and trust, almost without thinking. that a metal box will safely carry us...

Read more

How the Romans invented central heating

Central heating feels like a modern convenience, yet its core principles were mastered nearly two thousand years ago. Long before boilers, radiators and underfloor heating systems, the Romans...

Read more