The story behind medieval cranes powered by ‘Human Hamsters’

Long before engines and hydraulics powered modern construction, medieval builders lifted massive stones into place using human muscle alone. Inside towering cathedrals, workers walked inside giant wooden wheels - tread wheel cranes - hoisting blocks weighing tonnes. These human-powered machines, sometimes dubbed “medieval hamster wheels,” were the hidden force behind Europe’s most ambitious architectural feats, combining mechanical ingenuity with raw effort centuries ahead of the Industrial Revolution.

Though the concept of a wheel-powered lift dates back to Ancient Rome via the polyspaston. The polyspaston was an ancient Roman lifting device - a sophisticated type of pulley system used to hoist heavy loads, particularly in construction and engineering projects like temples, amphitheatres, and aqueducts. The tread wheel crane reemerged in the High Middle Ages around the 13th century when Europe needed a solution to lift heavy masonry to unprecedented heights. Archival records trace the earliest reference to a magna rota in France circa 1225, followed by depictions in illuminated manuscripts by 1240. England saw its first recorded use around 1331, as recorded in Wikipedia.

The Roman counterpart could lift 3,000 kg with four men at a windlass, and a tread wheel version could double that using fewer operators due to greater mechanical advantage. Medieval variants often matched or exceeded that efficiency, lifting multi-ton blocks with only a handful of human operators

Anatomy of a treadwheel crane

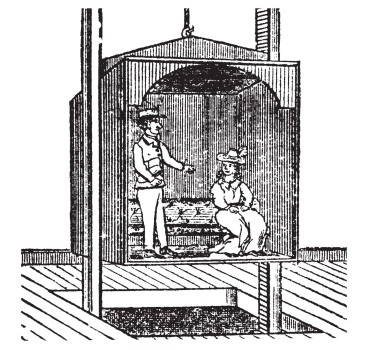

A typical medieval tread wheel was a wooden construct several metres in diameter, capable of accommodating one or two people inside walking in unison. The clasp-arm wheel design improved torque and efficiency over earlier compass-arm styles, allowing thinner shafts and higher leverage. As the operator walked, a drum or spindle around which a rope was wound lifted or lowered the load via pulley and jib arrangements.

Unlike modern cranes, these were predominantly vertical lifters. They seldom included ratchets or brakes - instead, their high friction and operator control slowed descent. Skilled crane masters directed lateral movement via guide ropes while the labourers inside walked the wheel.

One of the most striking traits of medieval crane use was its mobility. Towers were initially built at ground level, and once each floor was complete, the entire crane was dismantled and reassembled at the next higher level - moving bay by bay as the vaulting progressed. When construction ended, many machines remained in place in cathedral towers, serving later maintenance tasks.

These cranes were never mounted on fragile roof trusses or loaded scaffolding. Medieval engineers ensured proper support by placing the machines on the building’s solid interior framework or ground until the structure matured enough to bear their weight

The mechanical advantage was significant. A crane with a 14:1 advantage meant that a single person exerting force equivalent to 50 kg could lift roughly 3.5 tonnes - and double that with two operators or through better gearing. Larger harbour cranes used pairs of wheels and up to four operators to hoist as much as 7 tonnes. Yet being a treadwheel operator was arduous and dangerous. Workers, sometimes even blind men to avoid fear of heights, walked tirelessly in cramped, stooped positions inside wheels over 3 to 5 metres across. Walkers might travel 140 m inside the wheel to lift materials by just 10 m. Axle failures and falls were known risks.

Role in Gothic construction

Building Gothic cathedrals like Chartres, Salisbury, Cologne, or Strasbourg demanded a solution capable of lifting heavy masonry blocks into vaults pitched well above 20 metres. The tread wheel crane answered that call. Projects like Cologne Cathedral installed a slewing crane with two tread wheels rising 15.7 m and a rotating jib 15.4 m long. It remained in place from 1400 until its removal in 1842, effectively acting like a medieval tower crane

Surviving examples include the medieval crane housed in Canterbury Cathedral’s central tower, measuring 4.6 m in diameter and re-employed during renovation works in the 1970s. Similar machines remain at Beverley Minster, Guildford, and Harwich in England - some preserved as historic monuments.

Its return after the Roman era coincided with the rise of Gothic architecture. The need to lift heavier stones higher and within tighter spatial constraints prompted engineers to revive a powerful concept. Whether inspired by Vitruvius’ De architectura or reinvented empirically through observation of watermills, the wheel crane was recognised for its labour-saving potential.

Its mechanical principles aligned with existing windlass and pulley innovations from the Byzantine and monastic traditions. It offered a safer, faster, and more predictable alternative to ladders, hods, or manual hauling that coexisted on medieval building sites.

While vital in cathedral construction, tread wheel cranes also became staples in medieval ports. Harbour cranes in Bruges, Antwerp, Utrecht and Hamburg used dual-wheeled systems to load cargo from ships. These enclosed, permanent machines remained in use well into the early modern period and some even survived into the 17th century. Examples survive as listed structures in Harwich and Guildford.

In ironical contrast, by the 1800s, a darker version of the tread wheel appeared in prisons. English engineer William Cubitt’s treadmills forced inmates to walk endlessly, grinding grain or pumping water as punitive labour. The technology lived on, with human power no longer a means of creation but punishment.

Experimental archaeology projects like Guédelon Castle in Burgundy, France have reconstructed functioning medieval tread wheel cranes using only period-accurate tools and materials. These cranes lift mortar, stone blocks and timbers, demonstrating that such devices remain mechanically sound over eight centuries later.

Modern engineers and historians study these machines closely to understand weights, load curves and the exact choreography between crane masters and wheel-walkers. Records from Strasbourg Cathedral and Mont Saint Michel reveal wheels over four metres in diameter capable of lifting three tonnes while housing two operators.

An ingenious alliance of human and machine

In an era, devoid of motors, tread wheel cranes represent a creative coalition of muscle and mechanics. Their efficiency - able to lift tens of times more in weight than the operator’s effort - speaks to precise design. At the same time, they demanded precise coordination, because the crane master, the wheel-walkers, the ropes and the jibs had to be perfectly synchronised to avoid calamity. Far from quaint curiosities, these cranes were among the most advanced machines of their day - and central to the awe-inspiring heights of Gothic architecture.

Reflecting on the extreme demands of Gothic construction, the tread wheel crane offers several modern lessons. Mechanical advantage, modular design and vertical lifting remain central to modern construction cranes. And the power of early involvement, coordination, and skilled human operation still echoes in today’s planning and site logistics.

Moreover, the tread wheel’s eventual disappearance - replaced by steam, electric and hydraulic cranes - serves as a reminder that even the most optimal solution may yield to advancing technology. Yet a reconstruction like Guédelon proves that robust, thoughtfully engineered machines can endure beyond their era.

The image of medieval workers walking tirelessly within massive wooden wheels to haul stones skyward may seem surreal - like giant hamster wheels spun not for sport, but for sacred architecture. Yet these tread wheel cranes performed heavy lifting that otherwise would have required armies of men or impossible logistics.

From their resurgence in the 13th century through to the early modern age, these devices shaped not only how cathedrals rose, but how construction evolved across Europe. They stand as a testament to ingenuity, human coordination and the ability to extract enormous power from simple design.

Today, when we gaze up at Gothic spires or step inside attics of ancient churches and see preserved tread wheel relics, we glimpse an era when architecture danced on timber jibs, rope and human footsteps - an age when the muscle of man and wheel built monuments meant to touch the heavens.

Additional Articles

Why modern builders still use tools invented thousands of years ago

Walk onto a modern construction site and you will see plenty of laser levels, drones, tablets and power tools. Yet look a little closer and something unexpected becomes clear. Alongside all this...

Read moreThe elevator that changed the world when Elisha Otis cut the rope

Today, stepping into a lift is one of the most routine acts of modern life. We press a button, glance at the floor indicator, and trust, almost without thinking. that a metal box will safely carry us...

Read more

How the Romans invented central heating

Central heating feels like a modern convenience, yet its core principles were mastered nearly two thousand years ago. Long before boilers, radiators and underfloor heating systems, the Romans...

Read more