The genius who solved a 15th-century architectural puzzle

The Florence Cathedral, or Santa Maria del Fiore, is one of the most breathtaking architectural wonders in the world. However, its most famous feature - the dome that crowns the cathedral - was once considered an unsolvable architectural challenge. That was until Filippo Brunelleschi, a goldsmith and clockmaker with no formal architectural training, took on the impossible and forever changed the course of architectural history.

Construction of Santa Maria del Fiore began in 1296, designed by Arnolfo di Cambio. However, when Cambio passed away, the project was left incomplete, particularly the dome, which was meant to be the cathedral's crowning glory. The problem? No one knew how to build a dome of such a massive scale without traditional wooden scaffolding, which would have been impossible given the height and size required. By 1418, the cathedral had been standing roofless for over a century.

To solve this dilemma, the city of Florence announced a design competition. Several architects submitted proposals, but none were as daring or unconventional as Filippo Brunelleschi’s.

Who was Filippo Brunelleschi?

Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446) was a Florentine polymath with expertise in engineering, mathematics and art. Originally trained as a goldsmith and sculptor, he famously lost a competition to design the bronze doors of the Florence Baptistery to Lorenzo Ghiberti. Following this, Brunelleschi travelled to Rome to study ancient Roman structures, where he became fascinated with classical architecture and engineering.

Upon returning to Florence, he entered the dome competition in 1418 with an innovative proposal that promised to build the dome without wooden centring. This seemed impossible to many at the time, but Brunelleschi was convinced he had a solution.

Brunelleschi's dome was an unprecedented feat of engineering. He designed the dome as a double shell - an inner and outer dome connected by a network of ribs. This provided strength while reducing weight, making it lighter and more structurally sound.

One of Brunelleschi's most brilliant ideas was the use of a herringbone brick pattern, which allowed the bricks to self-support as they were laid. This pattern helped distribute the weight evenly and prevented the dome from collapsing inward.

Since traditional scaffolding was not feasible, he invented a complex hoisting system to transport heavy materials to great heights. Using gears, pulleys and ox-driven winches, his machines made construction more efficient and safer.

Most domes required a wooden framework to support the structure during construction, but Brunelleschi designed a dome that could hold itself up as it was built, reducing the need for extensive scaffolding.

Interlocking bricks and ribs

The dome features 24 ribs, eight of which are more prominent and serve as the primary supports. The bricks interlock to create a self-reinforcing structure that directs weight downward rather than outward, reducing stress on the walls. Brunelleschi further embedded a series of horizontal iron and wooden chains within the masonry to prevent the dome from expanding outward, much like modern tension rings used in bridges.

Understandably, Brunelleschi faced immense scepticism from Florentine officials and fellow architects. Many believed his techniques were too radical and doomed to fail. To prove his genius, he conducted a famous demonstration involving an egg, where he challenged his critics to stand an egg upright without support. When none succeeded, he cracked the egg slightly at the bottom, making it stand. The lesson? Once you know the trick, it seems simple, but it takes a visionary to invent it.

Throughout construction, Brunelleschi also dealt with political conflicts, particularly with his rival Lorenzo Ghiberti, who was initially assigned as a co-supervisor. However, Brunelleschi cleverly manipulated situations to assert control, ensuring that his vision remained unaltered.

After 16 years of construction, the dome was completed in 1436, standing 376 feet high and 138 feet in diameter - the largest masonry dome ever built. To this day, it remains the largest brick dome in the world.

Brunelleschi's masterpiece transformed not only Florence’s skyline, but also the entire course of architectural history. His innovations influenced Renaissance architecture, inspiring future architects such as Michelangelo (St. Peter’s Basilica) and Christopher Wren (St. Paul’s Cathedral).

Even today, Brunelleschi’s engineering principles continue to impact modern construction. His use of double shells and self-supporting structures can be seen in modern domes, from sports stadiums to government buildings. His hoisting mechanisms also laid the groundwork for modern cranes and lifting machinery used in skyscraper construction.

Brunelleschi’s dome is not just an architectural wonder - it is a symbol of human ingenuity and perseverance. By defying traditional methods and pushing the boundaries of engineering, Brunelleschi revolutionised architecture and left behind a legacy that continues to inspire.

His story reminds us that great innovations often come from those willing to challenge convention and that the most ambitious dreams can become reality with creativity, persistence and skill.

Additional Articles

Why modern builders still use tools invented thousands of years ago

Walk onto a modern construction site and you will see plenty of laser levels, drones, tablets and power tools. Yet look a little closer and something unexpected becomes clear. Alongside all this...

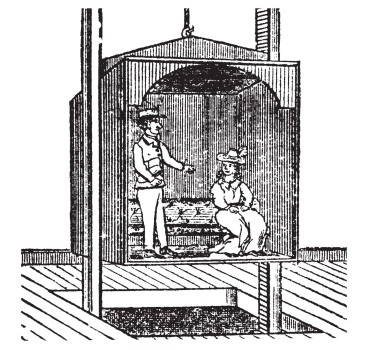

Read moreThe elevator that changed the world when Elisha Otis cut the rope

Today, stepping into a lift is one of the most routine acts of modern life. We press a button, glance at the floor indicator, and trust, almost without thinking. that a metal box will safely carry us...

Read more

How the Romans invented central heating

Central heating feels like a modern convenience, yet its core principles were mastered nearly two thousand years ago. Long before boilers, radiators and underfloor heating systems, the Romans...

Read more