Did our ancient builders use cow’s blood and beer as mortar additives?

In the long and varied history of construction, few details are as surprising - or as intriguing - as the unusual substances added to building materials. Among the most enduring legends are claims that medieval builders mixed cow’s blood and beer into their mortar to enhance the strength, durability, or workability of their structures. While such stories often drift into folklore, there is some evidence that these unconventional ingredients were more than just myth.

Mortar - the binding substance used to hold masonry units together - has evolved significantly over the centuries. Ancient and medieval mortar was typically made from a mixture of lime, sand and water. But because lime mortars cure slowly and are sensitive to moisture and weather conditions, builders often sought additives to improve curing times, workability, or longevity.

Modern analysis of historic structures has revealed a surprising variety of organic materials in old mortars. These include milk, egg whites, animal fats, plant extracts and yes, even blood and beer. The question is whether these ingredients were added deliberately for performance, or simply because they were available and customary in local recipes.

The use of animal blood, particularly cow blood, in mortar has been cited in various parts of the world, from Europe to Asia. Chemically, blood contains proteins - especially albumin - that can act as binders. When mixed into mortar, these proteins may influence curing behaviour and increase adhesion.

In India, for example, researchers have found that ancient builders added animal blood and jaggery (a type of unrefined sugar) to lime plasters. The tradition may have crossed into parts of Europe, where blood was occasionally added in areas with access to livestock and where cementitious materials were expensive or unavailable.

In one documented case, the 15th-century Masuleh village in Iran was found to have mortar containing blood proteins. Similarly, in Europe, anecdotal evidence and early texts suggest that small quantities of blood were added during specific phases of construction, potentially to act as a binding agent or even a primitive water proofer. It’s important to note that the use of blood would have been localised and relatively rare - both for reasons of availability and due to concerns over hygiene or religious restrictions.

Beer and ale in the mix

The use of beer or ale in construction mortar is also a subject of architectural curiosity. Like blood, beer contains organic compounds - such as sugars, enzymes, and yeast - that can influence chemical reactions in lime mortars. In theory, these compounds might accelerate the carbonation process, improve curing, or make the mix more pliable.

In medieval Northern Europe, where ale was consumed widely and often brewed on-site in manors, monasteries and even castles, there are recorded instances of it being used in construction processes. Some abbeys, such as those in Germany and the Low Countries, used beer in both food preparation and building maintenance.

Anecdotal references from the Hanseatic League period describe workers being “paid” partly in ale, some of which was reused in construction when fresh water was scarce or during winter months. While the volume of beer added was likely modest, its presence suggests builders were pragmatic, using what was at hand.

In England, there are also local building traditions, particularly in rural areas, where warm ale or even mead was occasionally added to mixes of daub or wattle and lime. These traditions likely blended practical knowledge with superstition and ritual.

While the idea of blood and beer in mortar may seem strange to modern sensibilities, ancient builders often relied on empirical methods, passed down through generations. Trial and error played a significant role in material science during the pre-industrial era.

It’s also important to distinguish between deliberate additives and incidental inclusion. In some cases, the presence of blood or beer could have been symbolic - part of a ritual marking the start of construction, especially in religious or monumental architecture.

In other cases, it may have been a matter of chemistry with the protein in blood acting as a plasticiser or the sugar in beer improving curing. There is also the possibility that these ingredients were added not for structural reasons, but for moisture regulation, pest resistance, or ease of mixing.

What science says

Modern analytical tools like Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) have allowed conservation scientists to examine historical mortars at the microstructural level. These analyses occasionally detect organic residues, but determining whether they were deliberate additives or environmental contaminants is not always straightforward.

Nonetheless, laboratory experiments have shown that mortars with added proteins -whether from egg, blood, or plant extracts - can indeed exhibit improved properties. They may resist cracking, bind more tightly to masonry, or better withstand freeze-thaw cycles.

One 2012 study in the Journal of Cultural Heritage examined proteinaceous additives in historic mortars and found that while rare, such mixtures did exist, especially in monastic or ecclesiastical buildings where precision and durability were paramount.

Many medieval buildings were constructed with elaborate rituals, including the blessing of stones or the placement of religious relics within foundations. It’s plausible that the inclusion of cow blood - seen as a life force - or beer - symbolic of abundance - carried ceremonial weight in certain regions or periods.

Even in modern times, certain rural traditions persist in parts of Eastern Europe and South Asia where symbolic offerings are still made during ground-breaking or cornerstone-laying ceremonies.

So, did builders really mix cow blood and beer into their mortar? The answer appears to be: occasionally and with good reason. While not widespread or standardised practice, historical records and modern analysis confirm that these unusual additives were sometimes used—whether for their chemical properties, practical availability, or symbolic meaning.

Far from being myths, these stories offer a glimpse into the ingenuity and resourcefulness of early builders. In an age without modern polymers, cement modifiers or ready-mix trucks, they relied on local materials, trial-and-error experimentation and centuries of evolving knowledge to create the structures that still stand today.

In many ways, these strange-sounding techniques reflect the intersection of construction science and cultural tradition - a blend of engineering, environment, and even superstition. For historians and conservationists, they are a reminder that innovation in building didn’t start with concrete mixers, but with the humble materials already in the hands of the builder.

Additional Articles

Why modern builders still use tools invented thousands of years ago

Walk onto a modern construction site and you will see plenty of laser levels, drones, tablets and power tools. Yet look a little closer and something unexpected becomes clear. Alongside all this...

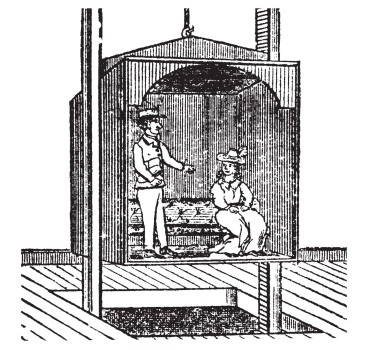

Read moreThe elevator that changed the world when Elisha Otis cut the rope

Today, stepping into a lift is one of the most routine acts of modern life. We press a button, glance at the floor indicator, and trust, almost without thinking. that a metal box will safely carry us...

Read more

How the Romans invented central heating

Central heating feels like a modern convenience, yet its core principles were mastered nearly two thousand years ago. Long before boilers, radiators and underfloor heating systems, the Romans...

Read more