Construction and the World’s first recorded labour strike

Buried within the history of ancient Egypt is a lesser-known, yet profoundly important milestone - the first recorded labour strike in human history. Far from a modern invention, organised worker protest was already taking shape more than 3,000 years ago - led not by political ideologues, but by skilled tomb builders under Pharaoh Ramses III.

The construction of Egypt’s monumental architecture - temples, tombs and pyramids - required vast human effort. Contrary to the popular myth of slave labour, much of Egypt's construction was carried out by trained, paid artisans, craftsmen and labourers. These men, particularly those who worked on the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings, formed a respected and skilled workforce. They were well-fed, housed in dedicated workers’ villages like Deir el-Medina and were provided with essentials in the form of food rations.

Their work was not only technically demanding, but spiritually significant. Preparing the burial places of pharaohs was a sacred duty, believed to ensure the eternal journey of the king in the afterlife. But despite the divine aura surrounding their profession, these workers were not immune to economic pressures or injustice.

The most detailed account of a labour strike comes from Deir el-Medina, a purpose-built village on the west bank of the Nile near Luxor, where the artisans responsible for constructing royal tombs lived and worked. During the reign of Ramses III (c. 1184–1153 BCE), these workers staged a series of protests over delayed payments - principally food rations.

The primary source for these events is the “Strike Papyrus” (also known as the Papyrus Turin 1880), written by the scribe Amennakht. It records a moment of social history that is strikingly modern in tone. When the artisans’ rations - consisting of bread, beer, vegetables, and fish - were delayed, they laid down their tools and walked off the job. They marched to the local mortuary temples to air their grievances, essentially staging a sit-in at sacred sites to make their point.

“We are hungry!”

The grievances were not theatrical - they were desperate. One account reads: “We are hungry... There is no clothing, no ointment, no fish, no vegetables.” The workers appealed to local officials, and then escalated their complaints up the chain of command. They were not violent, nor were they disorganised. Their actions were calculated and peaceful - a plea for fair treatment, not rebellion.

What makes this particularly significant is the bureaucratic reaction. The officials took the complaints seriously. Eventually, the rations were restored, and work resumed. But the episode set a historical precedent: workers had the power to pause a royal project through collective action.

Historical context is key. Ramses III’s reign, while initially strong, was marked by mounting internal pressures. Economic strain was evident as the empire’s wealth dwindled, partly due to military campaigns and foreign invasions, notably from the so-called “Sea Peoples.” Inflation and grain shortages were becoming common. There is also evidence of corruption and mismanagement within the bureaucracy that may have exacerbated the delays in worker compensation.

The strike didn’t emerge from nowhere - it reflected the broader economic instability of the time. However, it also highlighted a sophisticated administrative system where complaints could be logged, grievances addressed and outcomes negotiated, even in a deeply hierarchical society like ancient Egypt.

Early labour rights?

Some historians argue that the Deir el-Medina protest doesn’t constitute a “strike” in the modern industrial sense. It lacked unions, mass picketing, or formal contracts. However, by any functional definition, it was an organised withdrawal of labour in protest of unmet obligations. The workers understood their power and coordinated their actions to prompt change. Their strike was rooted in a clear social contract - labour in exchange for sustenance and shelter.

The protest reveals not only early ideas of workers’ rights, but also a glimpse into a society that, despite its authoritarian structure, acknowledged the importance of skilled labour and the potential consequences of its mistreatment.

The fact that these events were documented at all is a testament to the administrative sophistication of Ancient Egypt. The scribes of Deir el-Medina kept meticulous records - not just of construction tasks, but of daily life, complaints and legal proceedings. These records, written on papyrus and ostraca (pottery shards), provide an exceptional window into early labour relations.

The Deir el-Medina strike has since become a point of reference for archaeologists, labour historians and political theorists alike. It stands as evidence that the struggle for fair working conditions is ancient and perhaps innate to human civilisation.

The construction strike of Ancient Egypt is a reminder that even in the shadow of mighty pyramids and royal tombs, history is shaped by ordinary people demanding fair treatment. These artisans carved not only stone, but a path toward labour advocacy - centuries before the first trade unions or labour laws were established.

Their legacy persists in modern conversations about workers’ rights, fair pay and the value of skilled trades. At a time when construction and infrastructure projects continue to shape the modern world, the echoes from the Valley of the Kings remind us that behind every structure are people whose work deserves recognition, dignity and justice.

Additional Articles

Why modern builders still use tools invented thousands of years ago

Walk onto a modern construction site and you will see plenty of laser levels, drones, tablets and power tools. Yet look a little closer and something unexpected becomes clear. Alongside all this...

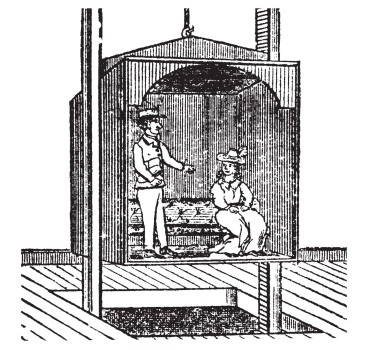

Read moreThe elevator that changed the world when Elisha Otis cut the rope

Today, stepping into a lift is one of the most routine acts of modern life. We press a button, glance at the floor indicator, and trust, almost without thinking. that a metal box will safely carry us...

Read more

How the Romans invented central heating

Central heating feels like a modern convenience, yet its core principles were mastered nearly two thousand years ago. Long before boilers, radiators and underfloor heating systems, the Romans...

Read more